Raider in the spotlight

Crew 1 - Pilot report James H. Doolittle

HEADQUARTERS OF THE ARMY AIR FORCES

WASHINGTON

July 9, 1942.

April 18, 1942

This report has been reproduced by the Intelligence Service, Army Air Forces, under the direction of the Commanding General, Army Air Forces and distributed as shown.

Futher dissemination in the Air Forces, except among the higher staff officers, is prohibited. Certain parts of thist considered sutable for wider dissemination are being extracted at this Headquarters and will receive wide sistriibution shortly in the form in Intelligence Summaries. The start and finish of the raid are believed still lunknown to the Japanese, and it is this information which it is desired to safeguard.

DISTRIBUTION:

| Copy | #1 | - | Original -- Files of the Director of Intelligence Service, Army Air Forces |

| " | #2 | - | General Doolittle |

| " | #3 | - | Military Intelligence Service |

| " | #4 | - | MIS for transmittal the Operations Division, WDGS |

| " | #5 | - | First Air Force |

| " | #6 | - | Second Air Force |

| " | #7 | - | Third Air Force |

| " | #8 | - | Fourth Air Force |

| " | #9 | - | Fifth Air Force |

| " | #10 | - | Sixth Air Force |

| " | #11 | - | Secenth Air Force |

| " | #12 | - | Eighth Air Force |

| " | #13 | - | Tenth Air Force |

| " | #14 | - | Eleventh Air Force |

All pilots were given selected objectives consisting of steel works, oil refineries, oil tank farms, ammunition dumps, dock yards, munitions plants, airplane factories. They were also secondary targets in case it was impossible to reach the primary target. In almost every case, primary targets were bombed. the damage done far exceeded out most optimistic expectations. A high degree of damage resulted from the highly inflammable nature of Japanese construction.

The first flight of three airplanes, led by lt. Hoover, covered the northern part of Tokyo; the second flight, led by Captain Jones covered the central part of Tokyo. The third flight, led by Captain York, covered the southern part of Tokyo. And the north central part of the Tokyo Bay area. The fourth flight, led by Captain Greening, covered the southern part of Kenegawa, the city of Yokohama and the Yokasuka Navy yard. The flight was covered over a fifty miles front in order to provide the greatest possible coverage to create the impression that there was a larger number of airplanes than were actually used, and to dilute any ground and air fire.

The fifth flight went around to the south of Tokyo and proceeded to the vicinity of Nogoya, where it broke up, one plane bombing Nogoya, one Osaka and one Kobe.

The joint Army-Navy bombing project was conceived, in its final form, in January and accomplished in April, about three months later. The object of the project was to bomb the industrial centers of Japan. It was hoped that the damage done would be both material and psychological. material damage was to be the destruction of specific targets with ensuing confusion and retardation of production. The psychological results, it was hoped, would be the recalling of combat equipment from other theaters for home defense thus effecting relief in those theaters, the development of a fear complex in Japan, improved relationships with our Allies, and a favorable reaction on the American people.

The original plan was to take off from and return to an aircraft carrier. Take off and landing tests conducted with three B-25B's at and off Norfolk, Virginia, indicated that take off from the carrier would be relatively easy but landing back on again extremely difficult. It was then decided that a carrier take-off would be made some place East of Tokyo and the flight would proceed in a generally Westerly direction from there. Fields near the East Coast of China and at Vladivostok were considered as termini. The principal advantage of Vladivostok as a terminus was that it was only about 600 miles from Tokyo against some 1200 miles to the China Coast and range was critical. Satisfactory negotiation could not, however, be consummated with the Russian Government and the idea of going to Vladivostok was therefore abandoned.

A cruising range of 2400 miles with a bomb load of 2,000 lbs. was set as the airplane requirement. A study of the various airplanes available for this project indicated that the B-25 was best suited to the purpose. The B- could have done the job as far as range and load carrying capacity was concerned but it was felt that the carrier take-off characteristics were questionable. The B-23 could have done the job but due to the larger wing span fewer of them could be taken and clearance between the right wing tip and the carrier island would be extremely close.

Twenty-four airplanes were prepared for the mission. Preparation consisted of installing additional tankage and removing certain unnecessary equipment. Three additional gasoline tanks were installed. First a steel gasoline tank of about 265 gallon capacity was manufactured by the McQuay Company and installed by the Mid-Continent Airlines at Minneapolis. This tank was later removed and replaced by a 225 gallon leak-proof tank manufactured by the United States Rubber Company at Mishawaka, Indiana. Considerable difficulty was experienced with this rubber leak-proof tank due to leaks in the connections and due to the fact that after having made one fairly satisfactory tank the outer case was reduced in size, in order to facilitate installation, without reducing the size of the inner rubber container and consequently wrinkles developed reducing the capacity and increasing the tendency to failure and leakage. Putting air pressure on the tank increased the capacity about ten to fifteen gallons and new outer covers alleviated the trouble. It was, however, not possible for the manufacturer to provide new covers for all of the tanks before we were obliged to take off. One serious tank failure occurred the day before we were to take off. The leak was caused by a failure of the inner liner resulting from sharp wrinkles which in turn were caused by the inner liner being too large and the outer case too small. room remained, in the bomb bay, underneath this tank to permit carrying four 500 lb. demolition bombs or four 500 lb. Incendiary clusters. It was necessary, in order to carry the bomb load, to utilize extension shackles which were also provided the McQuay Company. The crawl way above the bomb bay was lined and a rubber bag tank, manufactured by the U.S. rubber Company, and holding about 160 gallons was installed. The vent for this tank, when turned forward provided pressure and forced the gasoline out of the tank. When turned aft the vent sucked the air and vapor out of the tank and permitted it to be collapsed (after the gasoline was used) and pushed to one side. After this was done the ship was again completely operational as crew members could move forward or aft through the crawl way. Collapsing the tank, sucking out the vapor, and pushing it over to one side minimized the fire hazard. A very considerable amount of trouble was encountered with this tank due to leaks developing in the seams. This trouble was reduced through the use of a heavier material and more careful handling of the tank. The third tank was a 60 gallon leak-proof tank installed in the place from which the lower turret was removed. This tank was a regular 2'x2'x2' test cell with a filler neck, outlet and vent provided. The filler neck of this rear tank was readily available in flight. Ten 5-gallon cans of gasoline were carried in the rear compartment, where the radio operator ordinarily sat, and were poured into this rear tank as the gasoline level went down. These cans later had holes punched in them so that they would sink and were thrown overboard. This gave a total gallonage of 646 gallons in the main tank, 225 gallons in the bomb bay tank, 160 gallons in the crawl way tank, 60 gallons in the rear turret tank, and 50 gallons in 5-gallon tins, or 1,141 gallons, some 1,100 gallons of which were available. It might be pointed out here that all of the gasoline could not be drained from the tanks and that in filling them extreme care had to be taken in order to assure that all air was out and they were completely full. This could only be accomplished by filling, shaking down the ship and topping off again.

The extra tanks and tank supports were designed by and installed under the supervision of the Materiel Division of the Army Air Forces.

Two wooden 50 caliber guns were stuck out of the extreme tip of the tail. The effectiveness of this subterfuge was indicated by the fact that no airplane, on the flight, was attacked from directly behind. The lateral attacks were more difficult for the attacker and gave our machine gunners a better target.

De-icers and anti-icers were installed on all airplanes. Although these had the effect of slightly reducing the cruising speed they were necessary for insurance and also because it was not decided until shortly before leaving on the mission whether Vladivostok or East China was to be the terminus. Should East China be the terminus no ice was to be expected at lower altitudes but icing conditions did still prevail along the Northern route to Vladivostok.

When the turret guns were fired aft with the muzzle close to the fuselage it was observed that the blast popped rivets and tore the skin loose. As a result of this it was necessary to install steel blast plates.

Inasmuch as it was decided that all bombing would be done from low altitudes and the Norden bomb sight did not particularly lend itself to extremely altitude bombing, the bomb sight was removed and a simplified sight designed by Captain C.R. Greening was installed in its place. Actual low altitude bombing tests carried out at 1500 feet showed a greater degree of accuracy with this simplified sight than we were able to obtain with the Norden. This not only permitted greater bombing accuracy but obviated the possibility of the Norden sight falling into enemy hands. Captain Greening deserves special commendation for the design of this sight.

Difficulty was experienced in getting the lower turret to function properly. Trouble was encountered with the turret activating mechanism and with the retracting and extending mechanism. These troubles were finally overcome in large part. It was then found that the attitude of the gunner and the operation of the sight were so difficult that it would not be possible in the time available to train gunners to efficiently operate the turret. As a consequence of this, and also in order to save weight and permit the installation of the additional gas tanks, the lower turret was removed and a plate put over the whole where it stuck through the bottom of the fuselage.

We feel very strongly that in the present race to provide airplanes and crews in the greatest possible number in the shortest length of time that only equipment that is natural to use is satisfactory. Time does not permit the training of personnel to operate unnatural equipment or equipment that requires a high degree of skill in its operation. This thought should be kept in mind in the design, construction and operation of our new fire control apparatus.

Due to a shortage of 50 caliber ammunition the machine guns had not been fired and when we started training we immediately found that they did not operate properly. Some did not fire at all and the best of them would only fire short bursts before jamming. Mr. W.C. Olson from Wright Field was largely responsible for overcoming this difficulty. He supervised the replacement of faulty parts, the smoothing down of others, the proper adjustment of clearances and the training of gun maintenance crews. When we left on our mission all guns were operating satisfactorily.

Pyrotechnics were removed from the airplane in order to reduce the fire hazard and also for the slight saving in weight. Two conventional landing flares were installed immediately forward of the rear armored bulkhead. This gave a maximum of protection against enemy fire. There was no dropping mechanism for the landing flares. It was planned, if it became necessary to use them, that they be thrown out by the rear gunner. A lanyard attached to the parachute flare and the fuselage would ordinarily remove the case some 6 feet from the plane. It is suggested that pyrotechnics be installed against the armored bulkhead instead of along the sides of the fuselage.

Inasmuch as it was planned, in the interest of security, to maintain radio silence throughout the flight and weight was of the essence, the 230 lb. Liaison radio set was removed.

The lead ship and each of the flight leaders' ships were equipped with electrically operated automatic cameras which took 60 pictures and one-half second intervals. the cameras could be turned on at any time by the pilot and were automatically started when the first bomb dropped. Cameras were located in the extreme tip of the tail between the two wooden 50 caliber guns. Lens angle was 35°. As they were pointed down 157° the rearward field, in level attitude, covered 21/2° above the horizon and 321/2° below. In tests they operated perfectly. The other ten airplanes carried 16 m.m. movie cameras similarly mounted.

All special equipment such as emergency rations, canteens, hatchets, knives, pistols, etc. were made secure before take-off.

Special 500 lb. demolition bombs were provided, through the cooperation of Colonel Max F. Schneider of A-4, by the Ordnance Department. These bombs were loaded with an explosive mixture containing 50% T.N.T. and 50% Amatol. They were all armed with a 1/10 of a second nose fuse and a 1/40 of a second specially prepared tail fuse. The 1/10 of a second nose fuse was provided in case the tail fuse failed. 11 second delay tail fuses were available to replace the 1/40 f a second tail fuse in case weather conditions made extremely low bombing necessary. In this case the tail fuse was to be changed just before take-off and the nose fuse in that case would not be armed.

The Chemical Warfare Service provided special 500 incendiary clusters each containing 128 incendiary bombs. These clusters were developed at the Edgewood Arsenal and test dropped by the Air Corps test group at Aberdeen. Several tests were carried on to assure their proper functioning and to determine the dropping angle and dispersion. Experimental work on and production of these clusters was carried on most efficiently.

A special load of 50 caliber ammunition was employed. This load carried groups of 1 tracer, 2 armor piercing and 3 explosive bullets.

The twenty-four airplanes for the Tokyo project were obtained from the 17th Bombardment Group. Inasmuch as the airplanes had been obtained from this group and there were, therefore, crews available without airplanes, together with the fact that these crews were experienced in the use of these particular airplanes, the crews were also obtained from this source. It was explained to the Commanding Officer of the 17th Bombardment Group, Lt. Colonel W.C. Millis, that this was to be a mission that would be extremely hazardous, would require a high degree of skill and would be of great value to our defense effort. Volunteers for this mission were requested. More people than we could possibly use immediately volunteered. Twenty-four crews were ordered to Eglin Field for a final course of training. These crews together with the ground maintenance men, armorers, etc., proceeded to Eglin Field, Valparaiso, Florida, as rapidly as the airplanes could be converted and made available. The first of them arrived just before the first of March and the rest just after.

Concentrated courses of instruction were given at Eglin Field. The instruction included carrier take-off practice under the supervision of Lt. Henry Miller of the U.S. Navy. This practice was carried out on one of the auxiliary fields near Eglin. White lines were drawn on two of the runways of this field. Take-off practice was carried out with light load, normal load, and overload up to 31,0000 lbs. In all cases the shortest possible take-off was obtained with flaps full down, stabilizer set three-fourths, tail heavy, full power against the brakes and releasing the brakes simultaneously as the engine came up to revs. The control column was pulled back gradually and the airplane left the ground with the tail skid about one foot from the runway. This appeared to bet unnatural attitude and the airplane took off almost in a stall. In spite of the high wing loading and unnatural attitude the comparatively low power loading and good low-speed control characteristics of the airplane made it possible to handle the airplane without undue difficulty in this attitude. Only one pilot had difficulty during the take-off training. Taking off into a moderately gusty wind with full load, her permitted the airplane to side slip back into the ground just after take-off. No one was hurt but the airplane was badly damaged. While we do not recommend carrier take-off procedure for normal take-offs, it does permit of a much shorter take-off, and may be employed in taking off from extremely short or soft fields. With about a ten-miles wind take-offs with light load were effected with as short a run as 300 feet. With a normal load of 29,000 lbs. In 600 feet, and with 31,000 lbs. In less than 800 feet. The tact, skill and devotion to duty of Lt. Miller, of the U.S. Navy, who instructed our people in carrier take-off procedure deserves special commendation.

Special training was given in cross country flying, night flying and navigation. Flights were made over the Gulf of Mexico in order to permit pilots and navigators to become accustomed to flying without visual or radio references or land marks.

Low altitude approaches to bombing targets, rapid bombing and evasive action were practiced. Bombing of land and sea targets was practiced at 1500, 5000 and 10,000 feet. Low altitude bombing practice was specialized in. One hundred pound sand loaded bombs were used in the main but each crew was given an opportunity to live bombs as well.

Machine gun practice was carried on on the ground and in the air. Ground targets were attacked and it was intended to practice on tow targets as well but time did not permit. In order to get practice in operating the turret, pursuit planes simulated attack on our bombers and the gunners followed them with their empty guns.

The first pilots were all excellent. The co-pilots were all good for co-pilots. The bombardiers were fair but needed brushing up. The navigators had had good training but very little practical experience. The gunners, almost without exception, had never fired a machine gun from an airplane at either a moving or stationary tt.

In spite of a large amount of fog and bad weather which made flying impossible for days at a time and the considerable amount of time required to complete installations and make the airplanes operational at Eglin Field the training proceeded rapidly under the direction of Captain Edward York. In three weeks ships and crews were safely operational although additional training of the crews and work on the ships would have improved their efficiency.

On March 25, the first of 22 ships (one airplane, as previously mentioned was wrecked during take-off practice and another airplane was damaged due to the failure of the front wheel shimmy damper. While taxying normally the front wheel shimmied so violently that a strut fitting carried away and let the airplane down on its nose. Although the damage was slight there was not time to repair it) took off from Eglin Field for Sacramento Air Depot where the airplanes were to have a final check and the remaining installations were to be made. On March 27, all airplanes had arrived.

On March 31 and April 1, 16 planes were loaded on the U.S.S. Hornet alongside of the dock at the Alameda Air Depot. Although 22 planes were available for loading there was room on deck for only 15. 16 planes were actually loaded but it was intended that the 16th plane would take off the first day out in order that the other pilots might have an opportunity to at least see a carrier take-off. A request had previously been made of Admiral W.F. Halsey, who was in charge of the task force, to permit each one of the pilots a carrier take-off prior to leaving on the mission or to permit at least one pilot to take off in order that he might pass the information obtained on to the others. Admiral Halsey did not agree to this due to the delay it would entail. He did, however, agree to take one extra plane along and let it take off the first day out or the first favorable weather thereafter. It was later agreed to keep this plane aboard and increase our component from 15 to 16.

Training was continued n the carrier. This training consisted of a series of lectures on japan given by Lt. Stephen Jurika, Jr. of the Navy, lectures on first aid and sanitation by Lt. T.R. White, M.C. our flight surgeon, lectures on gunnery, navigation and meteorology by members of our own party and officers from the Hornet, and a series of lectures on procedure by the writer.

Actual gunnery and turret practice was carried on using kites flown from the Hornet for targets.

Celestial navigation practice for our navigators supervised by the Hornet navigation officer. Star sights were taken from the deck and from the navigating compartment in the airplanes. In this way a high degree of proficiency was developed and satisfactory optical characteristics of the navigating compartment window were assured.

A great deal of thought was given to the best method of attack. It was felt that a take-off about 3 hours before daylight arriving over Tokyo at the crack of dawn would give the greatest security, provide ideal bombing conditions, assure the element of surprise and permit arrival at destination before dark. This plan was abandoned because of the anticipated difficulty of a night take-off from the carrier and also because the Navy was unwilling to light up the carrier deck for take-off and provide a check lite ahead in these dangerous waters.

Another plan was to take off at crack of dawn, bomb in the early morning and proceed to destination arriving before dark. This plan had the disadvantage of daylight bombing presumably after the Japanese were aware of our coming and the hazards incident to such a daylight attack. The third plan, the plan finally decided on, was to take off just before dark, bomb at night and proceed to destination arriving after daylight in the early morning. In order to make this plan practical one plane was to take off ahead of the others, arrive over Tokyo at dusk and fire the most inflammable part of the city with incendiary bombs. This minimized the overall hazard and assured that the target would be lighted up for following airplanes.

Despite an agreement with the Navy that we would take off the moment contact was made with the enemy and the considerable hazard of contact being made during the run in on the last day we still decided to gamble in order to get the greater security of a night attack. As a matter of fact, contact was made in the early morning and we took off several hours after daylight.

The first enemy patrol vessel was detected and avoided at 3:10 a.m. on the morning of April 18. The Navy task force was endeavoring to avoid a second one some time after daylight when they were picked up by a third. Although this patrol was sunk it understood that it got at least one radio message off to shore and it was consequently necessary for us to take off immediately. The take-off was made at Latitude 35° 43'N Longitude 153° 25'E approximately 824 statue miles East of the center of Tokyo. The Navy task force immediately retreated and in the afternoon was obliged to sink two more Japanese surface craft. It is of interest to note that even at this distance from Japan the ocean was apparently studded with Japanese craft.

Final instructions were to avoid non-military targets, particularly the Temple of Heaven, and even though we were put off so far at sea that it would be impossible to reach the China Coast, not to go to Siberia but to proceed as far West as possible, land on the water, launch the rubber boat and sail in.

Upon take-off each airplane circled to the right and flew over the Hornet lining the axis of the ship up with the drift sight. The course of the Hornet was displayed in large figures from the gun turret abaft the island. This, through the use of the airplane compass and directional gyro permitted the establishment of one accurate navigational course and enabled us to swing off on to the proper course for Tokyo. This was considered necessary and desirable due to the possibility of change in compass calibration, particularly on those ships that were located close to the island.

All pilots were given selected objectives, consisting of steel works, oil refineries, oil tank farms, ammunition dumps, dock yards, munitions plants, airplane factories, etc. They were also given secondary targets in case it was impossible to reach the primary target. In almost every case primary targets were bombed. The damage done far exceeded our most optimistic expectations. The high degree of damage resulted from the highly inflammable nature of Japanese construction, the low altitude from which the bombing was carried out, and the perfectly clear weather over Tokyo, and the careful and continuous study of charts and target areas.

In addition to each airplane having selected targets assigned to it, each flight was assigned a specific course and coverage. The first flight of 3 airplanes, let by Lt. Hoover, covered the Northern part of Tokyo. The second flight, led by Captain Jones, covered the central part of Tokyo. The third flight, led by Captain York covered the Southern part of Tokyo and the North Central part of the Tokyo bay area. The fourth flight, led by Captain Greening, covered the Southern part of Kenegawa, the city of Yokahama and the Yokasuka Navy Yard. The flight was spread over a 50 miles front in order to provide the greatest possible coverage, to create the impression that there was a larger number of airplanes than were actually used, and to dilute enemy ground and air fire. It also prohibited the possibility of more than one plane passing any given spot on the ground and assured the element of surprise.

The fifth flight went around to the South of Tokyo and proceeded to the vicinity of Nogoya where it broke up, one plane bombing Nogoya, one Osaka and one Kobe.

The best information available from Army and Navy intelligence sources indicates that there were some 500 combat planes in Japan and that most of them were concentrated in the Tokyo Bay area. The comparatively few fighters encountered indicated that home defense had been reduced in the interest of making the maximum of planes available in active theaters. The pilots of such planes as remained appeared inexperienced. In some cases they actually did not attack, and in many cases failed to drive the attack home to the maximum extent possible. In no case was there any indication that a Japanese pilot might run into one of our planes even though the economics of such a course would appear sound. It would entail trading a $40,000 fighter for a $200,000 bomber and one man, who could probably arrange to collide in such a way as to save himself, against 5 who even though they escaped would be interned and thus lose their military utility. The fire of the pilots that actually attacked was very inaccurate. In some cases the machine gun gullets bounced off the wings without penetrating them. This same effect was observed when a train, upon which some of our crew members were riding in China, was machine gunned by a Japanese attack plane. One of the projectiles which had bounced off the top of the train without penetrating was recovered. It was a steel pellet about one inch long, pointed on one end and boat tailed on the other. It had no rifling marks and was apparently fired from a smooth bore gun.

The anti-aircraft defense was active but inaccurate. All anti-aircraft bursts were black and apparently small guns of about 37 or 40 m.m. size. It is presumed that the high speed and low altitude at which we were flying made it impossible for them to train their larger caliber guns on us if such existed. Several of the airplanes were struck by anti-aircraft fragments but none of them was damaged to an extent that impaired their utility of impeded their progress. Although it was to be presumed that machine gun fire from the ground was active, none of the crew members interviewed to date saw any such action nor was there evidence of machine gun fires in the bottom of any of the airplanes. A few barrage balloons were seen. One cluster of five or six was observed just north of the Northernmost part of Tokyo Bay and what appeared to be another cluster was observed near the Bay to the Southeast. These barrage balloons were flying at about 3000 feet and were not in sufficient numbers to impede our bombing. Japanese anti-aircraft fire was so inaccurate that when shooting at one of our airplanes in the vicinity of the barrage balloons they actually shot down some of their own balloons.

We anticipated that some difficulty might be experienced due to our targets being camouflaged. Little or no effective camouflage was observed in the Tokyo area.

We can only infer that as the result of an unwarranted feeling of security and an over-all shortage of aircraft and pilots, home defense had been made secondary to efficient operation in other theaters. It is felt that the indicated low morale of the Japanese pilots around Tokyo compared to the efficiency and aggressiveness of pilots encountered on the active front was the result of a knowledge on their part of the inadequacy of their equipment and their own personal inefficiency.

In spite of the fact that at least one radio message was gotten off prior to our take-off by the Japanese patrol boat that was later sunk -- that we passed a Japanese light cruiser (thought by one of the pilots to be a tanker) about miles East of Tokyo -- a Japanese patrol plane or bomber headed directly for our task force about 600 miles from Tokyo (this plane turned around and followed one of our airplanes so we know we were observed by it) and innumerable Japanese patrol and fishing boats from some 300 miles off-shore until crossing the Japanese Coast, the Japanese were apparently entirely unprepared for our arrival. Inasmuch as messages must have been received at some message center, we can only presume poor dissemination of information or the complete failure of their communication system.

As previously mentioned, the take-off occurred almost ten hours early due to contact being made with enemy surface craft. In addition to this, the take-off was made on the 18th instead of the 19th as originally planned and agreed due to the Navy getting one day ahead of schedule and the undesirability of remaining longer than necessary in dangerous waters.

We had requested a fast run-in at night and slow day progress in order that we might be within safe distance of Tokyo at any time during the take-off day. This was not expedient from a Navy viewpoint due to their poor maneuverability at slow speeds and the undesirability of running in any closer than was absolutely necessary.

We appreciated the desirability of advising Chungking of our premature take-off but due to the necessity of strict radio silence, this could not be done prior to our actual take-off. We requested that Chungking be advised immediately after we took off and felt that even though they were not advised by the Navy radio that the Japanese radio would give them the desired information. As a matter of actual fact, Chungking did know that we were coming but official information was not sent to Chuchow, presumably due to the extremely bad weather and the communication difficulties resulting therefrom. As a result of this no radio homing facilities were provided for us at Chuchow, nor were light beacons or landing flares provided. To the contrary, when our planes were heard overhead an air raid warning alarm was sounded and lights were turned off. This, together with the very unfavorable flight weather over the China Coast, made safe landing at destination impossible. As a result all planes either landed either near the Coast or the crews bailed out with their parachutes.

Before leaving China, arrangements were made with General Koo Chow Tung and Madam Chiang Kai-shek to endeavor to ransom the prisoners who had fallen into the hands of the puppet government. Some consideration was given to attempting the rescue of the prisoners that had fallen into Japanese hands in the vicinity of Payang Lake but it was indicated, due to the strong Japanese position, that at least two regiments would be required and that the chance of the prisoners being killed during the action was so great that the idea was abandoned. Negotiations were being carried on, when the write left China, to then end of offering small guerrilla bands a certain amount of money for each prisoner that they could bring out of Japanese occupied territory alive.

Several outstanding lessons may be learned from the flight. First, sufficient modern airplanes and competent pilots should be retained within the territorial limits of the United States to assure her adequate defense. Second, an absolutely infallible detection and communication system must be provided. Third, efficient utilization of small surface craft, such as fishing boats equipped with an extremely simple radio could, through the use of a simplified code, send messages to a message center indicating the type, position, direction of approach, speed and altitude of any enemy attacking force. Fourth, the necessity for suitable camouflage and adequate dissimulation. Fifth, the highest possible degree of dispersal in order that a bomb attack, if successful, will do the minimum amount of damage.

The desirability of stopping an enemy bombing raid before arrival over target is obvious. This can be accomplished only with a preponderance of fighters.

The successful bombing of Tokyo indicated that, provided the element of surprise is possible, an extremely successful raid can be carried out at low altitudes with great damage and high security to equipment and personnel.

/signed/

J.H. DOOLITTLE

Brigadier General, U.S. Army

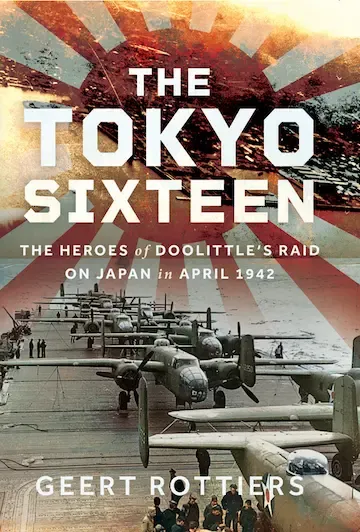

The Heroes of Doolittle's raid on Japan in april 1942

by Mr. Geert Rottiers

The book will be available soon.