Raider in the spotlight

At Sea

AT SEA

The departure of the mission

The United States had now devised and prepared a daring plan to attack Japan in retaliation for their attack on Pearl Harbor. The first 3 months of 1942 were spent planning and training for this attack. Eighty of the most experienced B-25 crews; technicians and supervisors were deployed for this volunteer mission. Everyone knew there was a chance they wouldn't return from the mission. It was time to embark on what would become one of the most important missions of the war. Preparations had been made and the crew were considered well capable of accomplishing the mission. However, the men still did not know in detail what their mission would be.

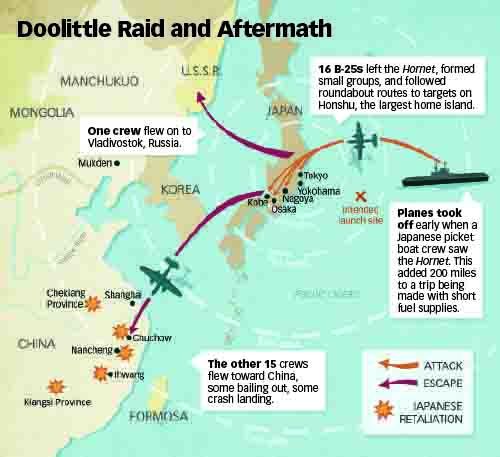

But of course they wondered, bombers on an aircraft carrier was unseen. Takeoff from an aircraft carrier with a bomber had also never been seen and performed during a mission or exercise, at least not in such a heavily loaded condition. Many people present in the port thought that the bombers had to be taken to a certain location to be deployed there. Sixteen B-25s were now loaded onto the deck of the USS Hornet in the middle of San Francisco Bay. And the squadron or convoy was not small. Some feared that the secrecy of the mission would be compromised by such visibility. The USS Hornet's Marines themselves were told they would transport the B-25s to Hawaii. A story that was not uncommon at the time. The B-25 crews knew better. The crews still had to wait for the more detailed plans of the mission, but they would be informed soon.

What was not discussed with Doolittle, but was understood by all, was the tremendous risk that the Navy was taking with this mission. If marauding Japanese submarines discovered the 16 ship force (Task Force 16 merged with Task Force 18 and became Task Force 16 commanded by Vice Admiral Halsey) steaming west, it would gain unprecedented opportunity to cripple what was left of the U.S. Navy's strength in the Pacific. Coupled with Japanese attack by long base bombers or heavy aircraft carrier force, it would mean the end of American Naval strength in the Pacific for months to come.

Task Force 18 left San Fransisco @ 2 April 1942 and consisted of the following ships: - click here -

Also two submarines were involved : USS Tresher-SS200 and the USS Trout-SS202. The USS Thresher departed 23 March 1942 for a patrol area near the Japanese home islands. There, she was to gather weather data off Honshū for use by Admiral William Halsey's task force ( (the carriers USS Enterprice and USS Hornet), then approaching Japan. De USS Trout-SS202 was in the same waters.

The USS Hornet at sea steaming direction Tokyo.

Lieutenant-Colonel Doolittle summoned his crews and their co-workers to the USS Hornet's only large conference room. He would explain the mission to them.

Captain Mitscher of the USS Hornet had made his quarters available to Jimmy Doolittle since he came aboard the USS Hornet. Doolittle was thankful for it. Captain Mitscher temporarily settled for one of the smaller cabins provided for officers. The ship's captain's quarters included a large meeting room on the ship where the crews and their employees could participate in the briefing. It was in this sole conference room on board where the crews could sit together.

Doolitlle spoke. “Nobody knows, maybe it's guesswork, I don't doubt it. We're going to Japan!" Doolittle informed them. Many crews looked at Jimmy Doolittle in disbelief - they were excited, but the mission was not greeted with cheers by the bomber crews either.

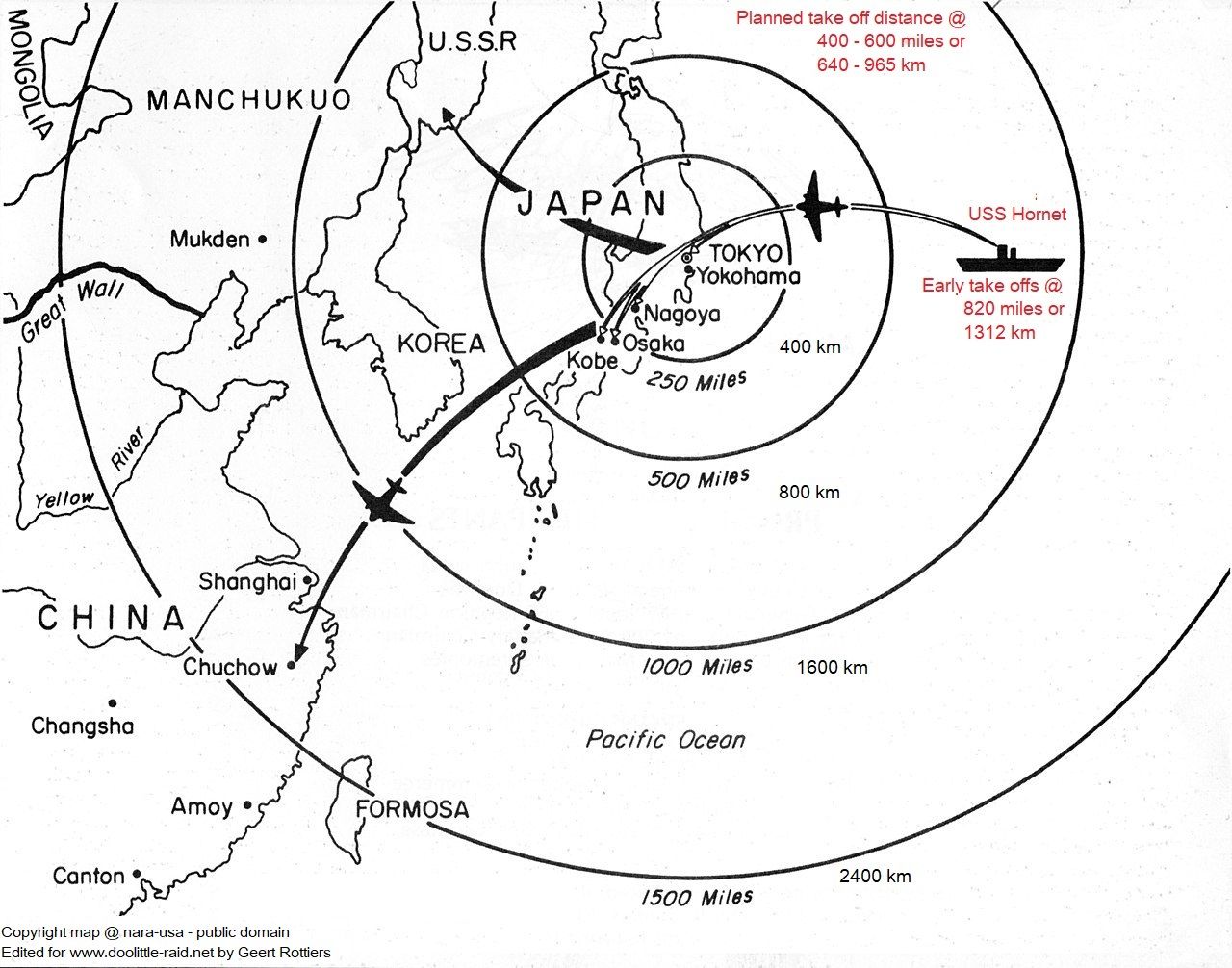

He then further informed the crews and their employees about the details of the mission. Doolittle and his crew would take off first on the B-25 from USS Hornet about 650 km (or 400 miles) off the coast of Japan. They would then fly over mainland Japan around dusk and a little later over Tokyo. Above Tokyo incendiary bombs (among other bombs) would be dropped on the munitions factories and other places, which was supposed to result in fierce fires. These fires would help the remaining waves of bombers find their targets over Tokyo. At least that was the plan.

Behind the small ship on the picture is the USS Hornet

Five flights of three planes each were scheduled to depart from the USS Hornet about three hours after Doolittle's first plane. Each crew (sixteen in total) was given the targets, located them on maps and compiled a list. The following days they would memorize the locations on the maps. The navigators were alerted to any landmarks before they were over Japan; the Inubo Saki lighthouse was one of those.

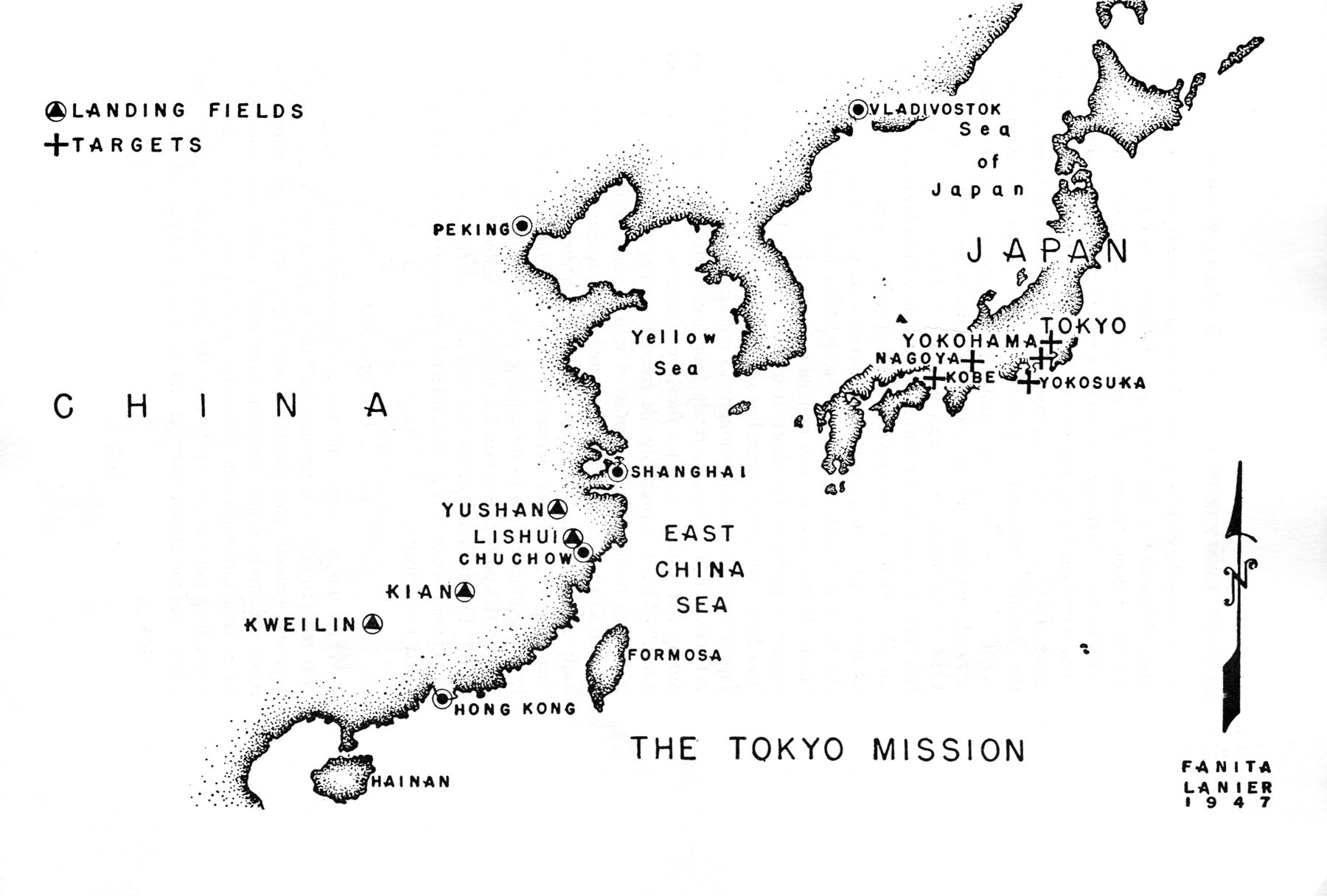

The B-25s would then continue flying to Chungking/Tsjoenking, China after dropping the bombs. This region in China was not occupied by the Japanese. The location was the temporary new capital of China as Peking/Beijing was occupied by the Japanese. It was the rendezvous point where the crews would meet and return to the US from. Preparations were made to refuel the bombers in China during the flight. Several airports were selected.

(map of landing strips in China below)

Mixed feelings ran through the conference room where Doolittle and the crews sat. The men were well trained and certainly ready for the mission, but at the same time the reality of the mission was beginning to dawn on them. It was certainly not a harmless mission. But they knew that from the start.

Japanes eaircraft carrier Hiryu

What would the Japanese do with them if they were captured when their planes were shot down by anti-aircraft fire? No doubt that they would be taken pow or maybe an execution would follow.

On 8 April 1942, the same day that the Americans and Filipinos defending Bataan Peninsula surrendered, Ethe USS Enterprise steamed slowly out of Pearl Harbor. With her escorts - the cruisers Salt Lake City and Northampton, four destroyers and an oiler - she turned northwest and set course for a point in the north Pacific, well north of Midway, and squarely on the International Date Line.

What the men in Enterprise's task force thought when USS Hornet and her escorts hove into view early 13 April 1942... Rumors spread about the force's mission: some tought the bombers were being delivered to a base in the Aleutians, while others speculated they were destined for a Russian airfield on the Kamchatka peninsula. The mystery was solved later in the day, when Vice Admiral William F. Halsey signaled that Task Force 16 - two carriers, four cruisers and eight destroyers, supported by two tankers and two submarines - was "bound for Tokyo."

At sea - part 2

Life on the aircraft carrier USS Hornet would soon become a grind. There is little to do and you cannot leave the ship to relax. The crews had daily briefings about their mission, they exercised on the deck of the USS Hornet and tinkered with their aircraft. Regular poker games became the usual occupation. The winnings from poker were used to buy supplies of cigarettes and candy bars on board the ship.

The bombers on board were under constant maintenance and were checked daily for minor defects and the engines were tested daily. Any problems found during regular inspections were immediately resolved.

The navigation panels were also replaced on board. These were delivered by balloon once the Task Force steamed into the ocean outside San Francisco.

Several photos of the ship show the B-25s tethered to the deck with engines sometimes running. The wind over the ship was too strong, so the bombers had to be secured on the flight deck.

Although supplies of spare parts were limited, any B-25 with a mechanical problem they couldn't fix would be pushed overboard. However, none of the crew wanted to lose their respective aircraft. With the help of the mechanics present, all technical problems were neatly solved. As well, with the help of sailors from the Navy, they tried to solve the small and large shortcomings themselves.

Of course, people also realized how important it was to have every B-25 aboard the USS Hornet go on mission. Since the B-25 could not descend into the hangar deck below the flight deck due to their weight, the crew built a tripod above the aircraft and installed a chain hoist system to support or extract the engines. This is also clearly visible in some photos.

Vice Admiral Halsey had departed Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on April 8, 1942, with Task Force 16. This was a few days later than expected due to organizational reasons. The delay of Task Force 16 coming from Pearl Harbor would also delay their encounter with Captain Mitscher's Task Force 18. Captain Mitscher made the necessary adjustments to his Task Force's course to accommodate this delay while sailing, both convoys would meet on 13 April at 38°00'00.0"N 180°00'00.0"E.

Unlike Captain Mitscher who informed his crew of their destination shortly after departure, Vice Admiral Halsey did not disclose the destination to Task Force 16. Many of the sailors on Task Force 16 were frustrated by the lack of information.

On 13 April 1942 the two groups met at sea and Vice Admiral Halsey officially took command of Task Force 18. Task Force 18 amalgamated with Task Force 16. The convoy continued as Task Force 16 with a total of some 10,000 crew members on sixteen ships.

"This force is bound for Tokyo."

Vice Admiral William F. Halsey, 13 April 1942

Rumors and speculation quickly spread about the purpose of the mission on the ships that departed Pearl Harbor with Vice Admiral Halsey. The crews did not have to wait long to have their questions about the purpose of their mission answered. Vice Admiral Halsey went to the Enterprise's loudspeaker and declared, "This force is bound for Tokyo". Cheers also rose from the various ships that came from Pearl Harbor this time, but there was also some disbelief. They thought it was banal that there were B-25 bombers on the deck of the USS Hornet. Impossible to let them take off from an aircraft carrier was the tenor among the crew members. They had never seen this.

The weather at sea was bad; terrible. Many crew members who were part of the crews of the B-25s became seasick. Day in and day out, the ships were surrounded and shrouded in a salty mist.

Sailing to the west, they crossed the international date line, 14 April 1942 was not experienced. It is always one day further west of the line of the date line than it is east of this line.

No one aboard the ships knew exactly how far they could get to Japan without being spotted by the enemy. A nervous tension rose aboard the ships as they approached their target. They could be attacked or discovered at any time and everyone was aware of that. They had a special delivery for Tokyo that needed to be delivered.

Some captains of the ships in Task Force 16 ordered their crews to throw all paper and other flammable materials overboard in the hope of making their ships less flammable. They also boarded up windows to partly protect them against bullet impacts.

Lieutenant Colonel Doolittle had set a limit of 960 km (or 600 miles) for mission success. The convoy had to be at least that distance from the Japanese coast for the bombers to take off. The fuel consumption of the aircraft was calculated accordingly. The bombers also had fuel on board with their built-in fuel tanks for that distance. Every additional meter or mile of flying distance would mean that Doolittle and his crews would not have enough fuel to reach the non-Japanese areas of China. So, it was very important that the USS Hornet and the accompanying ships could sail as close to Japan as possible.

On the morning of April 17, 1942, the oil ships refuelled the aircraft carriers and cruisers. After refuelling, USS Hornet and USS Enterprise, accompanied by the four cruisers, headed forward at high speed toward Tokyo. The other ships turned right towards Pearl Harbor.

On the USS Hornet, the bombs were carefully brought up from the bomb bay and loaded into the bombers while the machine gun ammunition was also loaded into the B-25s.

Task Force 16 was now in Japanese-held waters. Japan had deployed smaller boats (often fishing boats) that carried radio equipment. Any enemy ship or convoy spotted by these Japanese boats was reported by the crew of these boats to their mothership by radio. Which in turn relayed the positions and compositions of a ship or fleet of ships by radio to Japanese Army and Navy headquarters.

Tension aboard the ships of Task Force 16 rose by the minute. A Japanese air raid on Task Force 16 was certainly a possibility. The United States could not afford to lose battleships again, after Pearl Harbor.

The rough sea and bad weather did have some advantages. The chance of being spotted by other ships or aircraft became smaller. It later turned out that this was the case.

There was a form of fear and uncertainty among the crew members, they could now be attacked by Japanese units at any time.

It was agreed that if the convoy was spotted, the B-25 bombers from this location would immediately take off from the USS Hornet or be pushed off the ship to clear the deck for the fighters to lift up from the hangar deck. These would then be deployed in defence of Task Force 16 along with the fighters aboard the USS Enterprise.

Since they could be forced to take off at any moment after being spotted, the bombers were moved on deck and already put in take-off order. Lieutenant Colonel Doolittle's plane was in front. The bombers were, of course, still tethered to the flight deck of the USS Hornet. Even if the sixteenth bomber, which was at the rear of the deck and partially overhanging it, were the last to take off, the first B-25 would still have 143 meters (or 467 feet) to take off. That should be enough distance.

The crews were very well trained to get their B-25s airborne over shorter distances, but this time the stakes were high. They couldn't afford to make a mistake during take-off or crash into the sea.

The radio crews of the various ships of Task Force 16 were on high alert and tried to intercept messages sent by the enemy at sea to find out whether or not Task Force 16 had been detected.

The evening of April 17, 1942, the crews gathered on the flight deck of the USS Hornet, accompanied by a naval photographer.

A photgrapher of the US Navy was also on board. A photo was taken of each crew of the sixteen B-25s. These are the same photos that this website also uses. Unique and distinctive that such photos were taken for a mission by the crews.

The Heroes of Doolittle's raid on Japan in april 1942

by Mr. Geert Rottiers

The book will be available soon.