Raider in the spotlight

Workouts and training

Mission preparations in a full swing

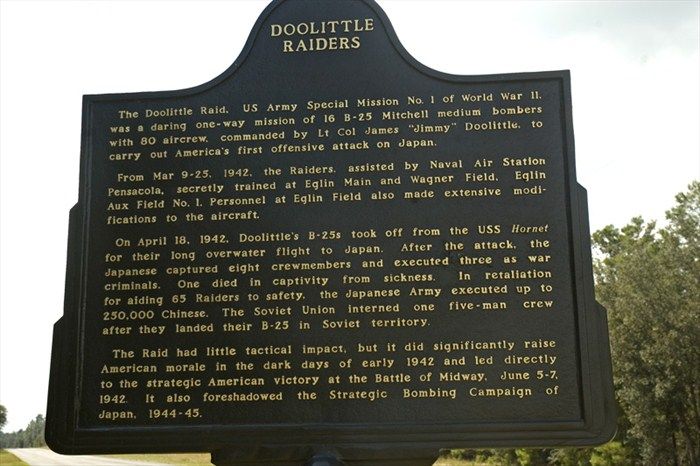

The airports in China and Vladivostok, Russia were approximately 950 km (or 500 miles) from Tokyo. It was feasible to land there, according to the creators of the raid's plans.

However, talks with Russia to allow passage to land and refuel on Russian territory in order to continue flying to China were met with a “no” from Russia because of their neutrality treaty with Japan.

So, the track in Russia where they would land and take off was abandoned. The United States even proposed to hand over those 16 B-25 bombers to the Russian Air Force once they arrived in Russia. But their “no” remained a “no”.

When they did the test flights in Virginia with taking off from the USS Hornet, it was concluded that taking off was possible. However, landing was technically almost impossible and entailed too many dangers. By the end of World War II, they did.

So, a minimal condition was that the mission could only carry on with bombers that had a range of at least 3900 km (or 2400 miles). The B-25 was selected as the bomber for the air raid on Japan.

In 1941, the B-25 bomber was new. By no means did every Bombardment Group in the United States have the B-25. At the time, only the 17th Bombardment Group had the necessary B-25s. They also had the most experienced B-25 crews. Their previous exercises and manoeuvres with the aircraft in Louisiana and Carolina made them the obvious choice to carry out the airstrike.

Logo 17th Bombardent Group

At the time Lieutenant-Colonel Doolittle decided to call in this unit, the unit had received orders to report to Savannah, Georgia for training with the aircraft. After all, the US was at war and they wanted to properly prepare the troops for their future missions with this new aircraft. But the last orders to fly to Georgia would be nullified. On February 3, 1942, just 24 hours after the successful test of the takeoff of both B-25s from the carriers, the commander of the 17th Bombardment Group, Lieutenant-Colonel William C. Mills, received a telegram. His orders were to immediately transfer the entire group of bombers to Columbia, South Carolina. The telegram also stated that volunteers were needed for "an extremely dangerous mission".

Almost every member of the 17th Bombardment Group volunteered without having any further substantive information about the assignment to be carried out. The crews were allowed to refuse to participate in the planned mission, without risking a sanction. So, they were free to participate or not to participate. But almost all still became volunteers.

As preparations for the first training sessions progressed, attention turned to crew selection. Doolittle knew that the mission would require fifteen B-25s and their crews. It would later appear that a 16th bomber and crew were kept in reserve to take off from the selected aircraft carrier, as a form of demonstration flight for the crews of the escort ships and the crews of the B-25 itself. It had to give them confidence that taking off from the USS Hornet was really possible. A total of 24 B-25 bombers and their crew participated in the preparations and training.

After the successful testing of the first launches of a B-25 from the USS Hornet aircraft carrier, 24 B-25s were modified to increase their range.

In February 1942, the 24 B-25s were flown to Mid Continent Airlines in Minneapolis, Minnesota for some modifications. And these were needed. In total, changes would be made to the B-25s at three different times during the preparations. It was also in Minneapolis that the unusual "broomstick" tail guns were added. To make the aircraft lighter, the machine guns at the rear of the aircraft were replaced by broomsticks to give the impression that the machine guns were still there. This was to discourage Japanese fighters from attacking the B-25 from behind when the B-25s flew over Japan. We will come back to that later.

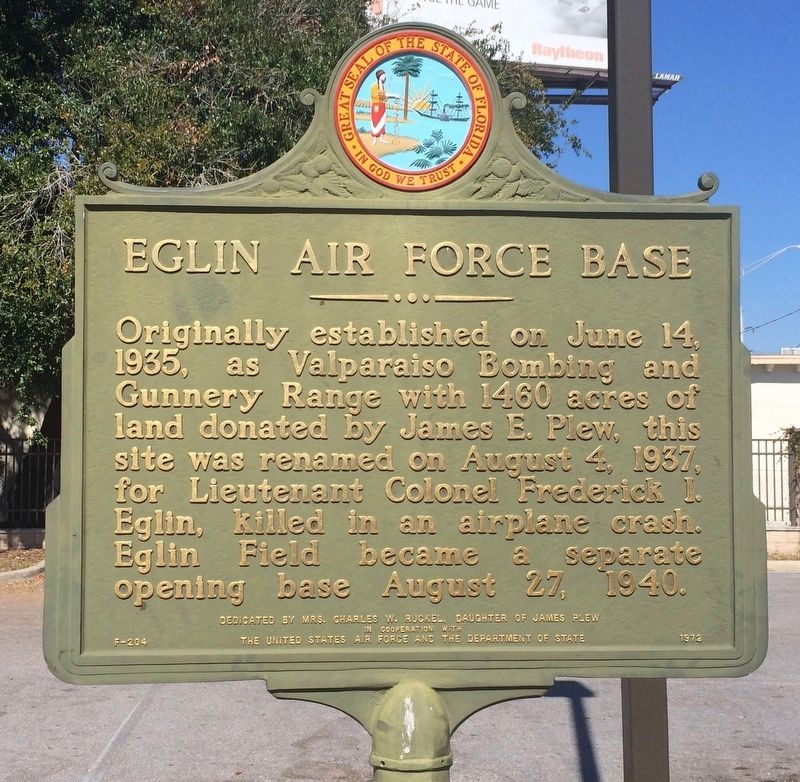

Afterwards, the B-25s flew to Eglin Field near Panhandle in Florida.

Eglin Field, Florida

After completing initial modifications to the 24 B-25s prepared for the attack, the 17th Bombardment Group was transferred to Eglin Field near Panhandle, Valparaiso, Florida.

The crews of each of the 17th Bombardment Group's four squadrons, along with the necessary mechanics and support personnel, were to be based at Eglin from 27 February through 3 March with their modified B-25s to practice at Eglin and carry out the raid as preparation. Eglin Field was a relatively remote base in Panhandle, Florida.

The proximity to the ocean would also allow navigational training over water. It was here that training for the raid became intensive. Taking off between the contours of an aircraft carrier whose contours were painted on the ground. There would also be some minor adjustments to the bombers.

On March 3, 1942, the 17th Bombardment Group would meet Lieutenant Colonel Jimmy Doolittle for the first time. Although Lieutenant Colonel Jimmy Doolittle did not divulge the detailed content of the mission, he made it very clear to the crews that the mission would be extremely dangerous and that it would only go ahead with volunteers. What he also made clear was that Japan would be the target.

Doolittle reiterated that anyone could leave training at any time without any sanctions and without any negative impact on their career in the Army. Not one crew member dropped out and all wanted to participate in the mission unknown to them. Also, no one really asked out loud what they were doing at Eglin Field and what they were practicing for. The mission had to remain secret to prevent Japan from being informed of it in any way.

Although a small leak or eavesdropping action must have taken place somewhere, because somehow Japan had learned through a partly deciphered radio message that something was about to happen around April 15, 1942 (not April 20).

Also at Eglin Field, Lieutenant Colonel Doolittle assigned crews to aircraft. He selected the crew members based on their training, leadership skills and courage. The training and preparation took place for the various disciplines. Doolittle wanted to select the best at all costs.

An addition to the group of the 17th Bombardment was Lieutenant Henry Miller. Lieutenant Henry "Hank" Miller was a naval instructor from nearby Pensacola, Florida. His arrival on March 1, 1942, the 17th then became active at Eglin Field, met with some skepticism. He had to teach the army crews how to take off from aircraft carriers and teach them the customs of the United States Marine Corps.

I have a web page about Lieutenant Henry "Hank" Miller - click here -

In full preparation

The participants in the preparation had not been told that their mission would start from an aircraft carrier. Many in the group were not convinced that a B-25 could be launched from an aircraft carrier.

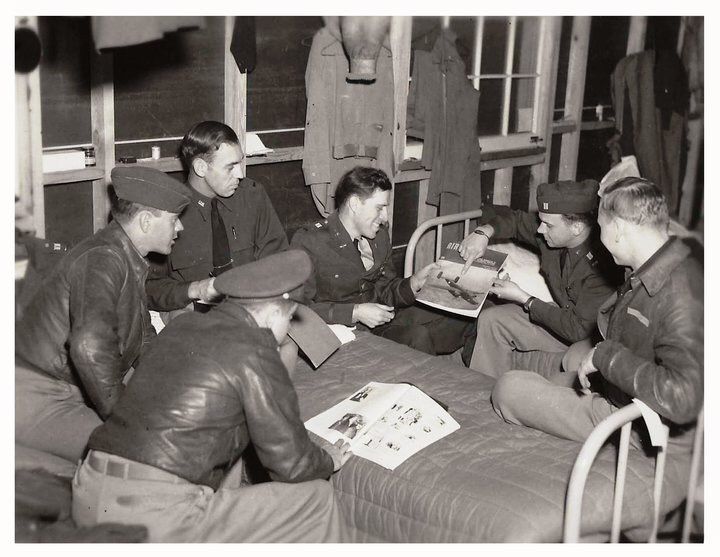

In the barracks at Eglin Field : Richard Joyce, Richard Cole, Henry Potter, William Fitzhugh (holding magazine) and Carl Wildner. Person with back on the picture is unknown to me.

The fact that Lieutenant Miller had never seen a B-25 until he arrived at Eglin Field did not inspire confidence in the crews. But Lieutenant Miller climbed into the co-pilot's seat of a B-25 and took the controls from Captain York. Following standard naval procedure, the B-25 took to the air. However, at less than half the usual speed. Lieutenant Miller quickly won the respect of the training select crew members.

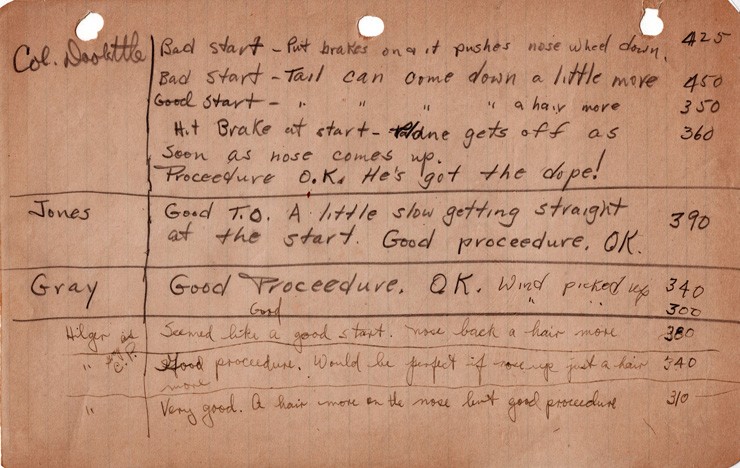

The pilots and co-pilots concentrated and trained relentlessly on the short field starts/take offs. As mentioned, the contours of an aircraft carrier had been painted on the ground on a runway. This to simulate a flight deck. Flags were placed as markers with the primary goal of being in the air at 243 meters (or 800 feet). After a week of practice, just about everyone was prepared to take off from 121 meters (or 400 feet) and be airborne at that distance.

Some form of competition was established between most pilots as each pilot wanted to take off at the shortest possible distance. The winner of the competition was Lieutenant Donald Smith who was able to get his B-25 airborne at 88 meters (or 287 feet) - Picture = notes of Miller.

Even Lieutenant Colonel Doolittle took Naval Instructor Lieutenant Henry "Hank" Miller's advice and comments more than seriously and became adept at getting a B-25 airborne below 800 feet as well. Lieutenant Hank Miller became a welcome figure among the crews of the B-25s that practiced at Eglin Field. He commanded a lot of respect.

Navigators were also trained and taught at Eglin Field. Speed tests were performed over various distances to calibrate the airspeed indicators. Each B-25's magnetic compass was also accurately calibrated. The navigators were trained in celestial navigation with sextants.

Training flights were flown over sea. Long training flights from Eglin Field, Florida to Fort Meyers, Houston and back were conducted at night in a variety of ways. The navigators would have the most accurate equipment and intensive training available during the raid.

Bombardier training was certainly equally challenging. While the crew was still unaware of the details of the mission, they would practice dropping bombs at low altitudes. Bombings usually consisted of dropping practice bombs, filled with concrete and sand, over an area now known as Fred Gannon State Park.

Each B-25 was equipped with the state-of-the-art Norden bomb aimer to drop the bombs in the right place. Although the bomb aimer was very accurate at high altitude, it became useless in the practiced flights at low altitudes at high speed. However, Lieutenant Ross Greening would design a simple solution using two pieces of aluminum. His bomb aimer, named after the "Mark Twain", proved to be very effective; this adjustment also happened in all 24 aircraft.

Initially, one of the main concerns was the state of the machine guns in the B-25s. Due to a shortage of ammunition, most of the machine guns had never been used. Some of them even jammed after a few rounds of firing and others didn't fire at all.

The machine gun turrets in the domes themselves were also a problem. They were electrically operated but very slow to respond. The lower tower was very difficult to operate. It took far too long for the machine gun to fire.

It was also found that firing ammunition close to the fuselage broke the rivets of the aircraft and damaged the bombers.

All these problems would be solved, but the solutions took time.

Machine guns

Although the gunners practiced on the ground with .50 caliber machine guns, they would fire very few shots from the air.

Controlling fuel consumption was a critical part of the flight engineer's job during training. While the crews were still not fully aware of their final destination, they were told they would fly over 1,900 miles during the mission. This also required modifications to the B-25 and the use of techniques to reduce fuel consumption. Detailed logs were kept to calculate and chart the fuel consumption of each aircraft. Significant differences in fuel consumption were noted. One cause of this problem was the propellers. For example, new propellers could in some cases increase airspeed by as much as 88.5 km/h (or 55 mp/h).

The Doolittle Raiders Hihway near Eglin.

The main change of the aircraft would be the carburettors.

A new cruise control map was created to maximize range by adjusting the B-25's propeller settings, among other things. The company's detailed records indicated that the B-25s consumed 295 liters (or 78 gallons) of fuel per hour when fully loaded. This would decrease to 246 liters (or 65 gallons) per hour as the bomber's weight decreased.

Lieutenant Thomas White, a surgeon by training, had also volunteered for the raid. He was told that there was no room for a doctor on this mission. However, he was given the opportunity to earn his way into one of the crew members through intense practice as an air gunner. He scored the second highest of all air gunners on the firing range, thus earning his place in the mission. Lieutenant Thomas "Doc" White would later on perform an amputation of the leg of one of the pilots as a medic during the mission.

There was no system on board that could drop flares to mark out a landing site in the dark. The flares were on board but had to be thrown out manually at the rear if necessary.

Several other things were noticed during practice and training, such as the navigation windows that needed to be adjusted. These windows were also ordered and later shipped to McClellan Field, Sacramento, California, where the B-25s would fly from Eglin just before they flew to California to be lifted onto the USS Hornet. Final preparations for the mission would be made in Sacramento.

General Arnold had a coded message sent to Eglin Field from the USS Hornet, who was at that time close to the Panama Canal and en route to California: "Tell Jimmy to get on his horse".

Ready or not (but they were), it was time for the crews to finish their training and depart for California where they would board the USS Hornet when it docked there.

At 3 a.m. on 23 March 1942, Jimmy Doolittle informed the crews to fly to McClellan Field in Sacramento for final adjustments and preparations.

This would also be their last training flight. The 22 crews (two aircraft were written off due to accident at Eglin Field) and aircraft that remained would fly over the country at very low altitude (treetop altitude). As they flew from Florida to California at 300 meters, cattle stampeded and farmhands ran away in fear. Even the unsuspecting walkers and sportsmen did not know what they saw and ran away afraid to hide somewhere.

The flight crews apparently had a lot of fun on this flight. For many it was an unforgettable flight that was later described by many participating crew members in their memoirs. The flight to Sacramento took many hours. The distance between the two locations is, to say the least, far.

Accidents at Eglin Field taken from https://b-25history.org/doolittle/training.htm

The challenge of learning short field takeoffs in such a short period of time did have consequences. The first of those incidents happened during a navigation flight. In the afternoon of March 10, 1942, B-25B SN 40-2254 suffered a nose wheel failure after landing at Ellington Field, Texas. None of the 6 men on board were injured. Pilot Richard O. Joyce had just landed and the aircraft developed a severe shimmy in the nose wheel about 400 feet from the end of the runway. Power was cut to the engines and the nose wheel collapsed. It was determined the cause was a malfunction of the shimmy dampener on the nose landing gear. The aircraft would eventually be repaired, but it would not return to Eglin during training.

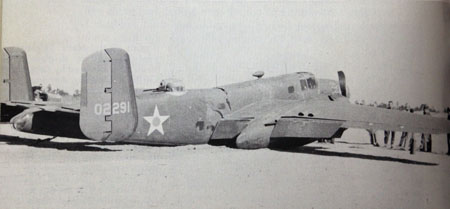

The second accident happened on the final day of training. The pilot was First Lieutenant James P. Bates. Lieutenant Miller felt Lt. Bates needed more practice on short field takeoffs. A crew was assembled to include Lt. Miller and loaded into B-25B SN 40-2291. While attempting to take off on the morning of March 23, 1942, the airplane stalled at about 15 to 20 feet in the air. The B-25 crashed severely damaging the airframe. All of the occupants were uninjured. The plane was damaged beyond economical repair and was scrapped. First Lt. Bates, Second Lt. Roloson, and Sgt. Roasch would not participate in the raid. The loss of the second plane caused Captain York to phone the headquarters of the 17th in Columbia. He asked his close friend Lt. Emmens to fly another B-25 to Eglin as a replacement. It should be noted that this B-25 would not be modified for the raid. Due to the nature of this request, no orders for this transfer were issued. As a result, the SN of this B-25 is lost to history.

On 23 March 1942, the crews took off with their planes from Eglin Field in Florida to McCallen Field Sacramento in California. There, all propellers were replaced and painted. The pilots of the bombers did not want the propellers to shine because of their silver colour. That gave too much reflection in the cockpit. Therefore, the propellers were painted over. They were also not allowed to abrade them with sandpaper because it was thought that the salty seawater could affect the propellers so that they broke off.

The planes received a final check-up before being loaded onto the aircraft carrier in San Francisco at Almeda Air Force Station. The last training flights were made in Sacramento Valley.

The carburettors of the aircraft were all adjusted once again to the mission to be performed so that lower fuel consumption became possible.

As stated earlier, a consumption of 295 liters per hour (or 78 gallons) at full weight was calculated. Later at a lighter weight that would be a consumption of 246 liters per hour (or 65 gallons). Ascent speed was determined to be between 105 and 110 miles per hour (or between 168 and 177 km). However, the take-off speed from a plane would be lower. There was also training and practice at night.

Carburetor adjustments were not the only problem for the participating crews. At McClellan Field, they had other problems. Doctor Thomas White pleaded for the necessary supplies for his medical kits. In his report, he noted that in many cases the desired supplies were on the shelves at McClellan Field, but the medical supplies officer refused to give them up for the mission. The group also had problems obtaining the necessary ammunition.

Another 227 liters (or 60 gallon) rubber bag that replaced the lower gun turret would also be installed at McClellan Field. Everything had to go fast. The USS Hornet was almost in San Francisco for loading.

The liaison radios and tracking antennas were removed from the aircraft. This mission was to be conducted in radio silence. The extra weight wouldn't be necessary.

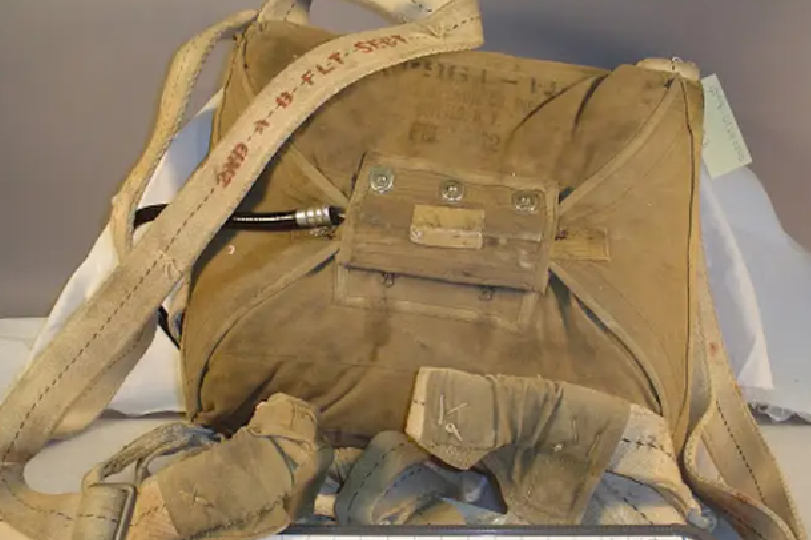

Parachutes were ordered and fitted. Photo cameras were placed in six of the B-25s to assess bomb damage. The other sixteen would be given film cameras.

Doolittle also ordered all burnt-out instrumentation lamps replaced. He requested that as many smaller spare parts as possible be placed in the aircraft. Soon they would be on their own.

Lessons and lectures were given on hygiene and customs in China (by Dr. T. White, who had meanwhile been appointed flight surgeon) and Japan (by Lieutenant Stephen Jurika).

There wouldn't be enough time to complete the changes to the carburettors. However, the adjustments were almost all complete.

However, some parts, such as the promised replacement navigation panels, did not arrive in Sacramento. These would be air shipped to the USS Hornet which would have already left on mission, delivery would be made just outside San Francisco Bay.

A table of those responsible for the mission was also drawn up. That looked like this:

|

Project commander Executive Officer Operations Officer Navigation-Intellegence Gunnery and bombing Engineering Officer Supply Officer 1st Flight Commander 2ndt Flight Commander 3rd Flight Commander 3rd Flight Commander 3rd Flight Commander Navy Liaison Officer |

Lieutenant colonel James Doolittle Major John A. Hilger Captain Edward J. York Captain David M. Jones Captain Charles R. Greening Lieutenant William M. Bower Lieutenant Travis Hoover Lieutenant Travis Hoover Captain Edward J. York Captain David M. Jones Captain Charles R. Greening Major John A. Hilger Lieutenant Henry L. Miller |

Naval Air Station Alameda (NAS Alameda) in California

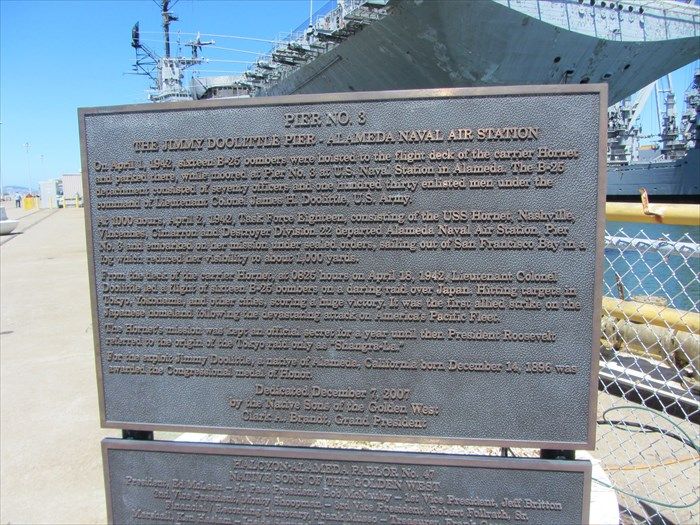

On the afternoon of 1 April 1942, the men flew to the Alameda Naval Air Station, also in California, where 16 of the 24 B-25 bombers would eventually be craned off the USS Hornet. Of the 24 bombers, 2 were decommissioned at Eglin Field, Florida. Six B-25s could not take part due to lack of space.

Naval Air Station Alameda in California was a US Navy base where, among other harbor related things, fighter aircraft were hoisted onto aircraft carriers using cranes and ship cranes.

The airport was built in 1927 on swampy ground and functioned as a civil airport in California. On June 1, 1936, it was taken over by the US Navy (the Air Force was part of the US Army at the time) because of the excellent location of this airport.

Many aircraft carriers docked there to load or unload or wait for further orders. This base was closed in 1997. This after serving during World War 2, the Korean War; the Vietnam War and the Cold War. Many hundreds of civilians were employed there.

After the arrival of Doolittle's B-25s on the afternoon of 1 April 1942, the pilots were asked if they had encountered any minor problems during the flight from Sacramento, California to Naval Air Station Alameda. The bombers safely taxied to the dock where the USS Hornet was docked to be loaded onto the ship. The bombers with smaller problems had to taxi to the hangars to be checked there. Afterwards, these aircraft were also loaded onto the USS Hornet.

Replacements for the designated current crews were also on board. Sixteen B-25 bombers were loaded onto the USS Hornet, but several full-fledged crews boarded it. In the event of illness or withdrawal from the mission at the last minute of the designated crews, these individuals could fill in. Mechanics and general maintenance personnel will also board with the bomber crews.

By taking all trained crews on board, Doolittle hoped to better preserve the secret nature of the mission. The crews that would not fly the mission could also e deployed as guardians of the B-25 bombers on board and thus be called in as maintenance technicians.

Pilot Captain Edward York of Crew 8 and co-pilot Lieutenant Dean Davenport of Crew 07 were apparently very excited that the mission was now going for good.

To the bewilderment of many, they flew their respective B-25 bombers under the iconic Golden Gate Bridge near San Francisco as they flew from Sacramento to Alameda. Too crazy for words and never seen with such planes. Co-pilot Lieutenant Dean Davenport of Crew 07 wanted to fly a second time under the bridge to put it on camera but pilot Ted Lawson of Crew 07 refused to do so.

Edward York

However, most members of the aircraft crews boarded the USS Hornet as aircraft maintenance personnel and as backups in case of illness among the selected crews. In total, about 140 army personnel boarded the USS Hornet. The sailors of the ship did not know what the army men came to do aboard the ship. A motley crew of military personnel on a Navy ship was not an everyday sight. And what did the 16 bombers that were hoisted aboard and stood on the flight deck of the USS Hornet do? It was incomprehensible to the sailors of the USS Hornet. The story circulated among the harbor personnel and sailors that the B-25 bombers were to be delivered to Pearl Harbor.

To lift 16 B-25 Mitchell bombers aboard the USS Hornet on 1 April 1942 the USS Hornet was docked @ pier 3 - these days known as the Jimmy Doolittle Pier – Alameda Naval Air Station Pier No. 3 - Alameda, California. Dedicated 7 December 2007

Further reading - menu USS Hornet - at sea

Pictures @ Eglin Field during the training taken by J. Roden Stork for USAAF - copyright @ usaf - public domain

The Heroes of Doolittle's raid on Japan in april 1942

by Mr. Geert Rottiers

The book will be available soon.